Home > River to Rail > Before Steam

River To Rail: Before steam

The Ohio River: America's Great Highway

Flowing nearly 1,000 miles from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to Cairo, Illinois, the Ohio River was and still is one of the most important means of transporting people and goods in the Eastern and Central United States. First extensively used by Native Americans, the Ohio took on an even greater economic and strategic significance with the arrival of European traders and settlers. By the time of the American Revolution, expansion into the unknown West was already well underway and the Ohio River was the path taken by many to reach this new world

Madison and La Belle Riviére

Like other river towns, Madison, Indiana, owes a debt of gratitude to the river that made its existence possible. From the earliest settlers who ventured west to take up residence as unauthorized colonists to the founders of the city to its most distinguished citizens, the Ohio River proved to be their ticket to a new life.

From Glacial Meltwater

Formed from glacial meltwater during the end of the last Ice Age, the Ohio overtook parts of the earlier Teays River’s course as it came to occupy its present channel. From this beginning, the Ohio became the dominant American waterway west of the Appalachians and east of the Mississippi.

With the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers as its source, the watershed of the Ohio covers nearly 500,000 square kilometers in 14 states.

Innate Beauty

Fed by more than 20 major tributary rivers, the area through which the Ohio flows once sustained a vast and trackless forest in which numerous Native American tribes flourished. In some places remnants of this once-enormous forest endure, and from these few picturesque areas, the banks of the Ohio can be transported back to their natural glory, if only in the mind’s eye.

Known to early French explorers as “La Belle Riviére” because of its gentle curves and the innate beauty of its wooded banks, the Ohio River enchanted the first Europeans to see it. Other less aesthetically-minded Europeans valued the river for its easily discerned ability to carry vast amounts of travelers and goods.

981 Miles

At 981 miles (1,579 km) in length, the Ohio River runs generally southwestward from its source at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to its mouth at Cairo, Illinois. Its meandering route winds through six states before ultimately merging with the Mississippi River.

As a direct result of its course, many large cities and towns dot the banks of the great river, among them the modern metropolises of Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and Louisville. However, in the early days of European colonization and American independence, the major cities along the river were the so-called gateway cities. These settlements were situated along easily accessible shipping routes and served as the gateway to the more remote interior lands. The location of these gateway cities afforded an easy means of transportation for the goods that were brought in from the hinterland. The city of Madison, built on the river’s north bank beneath heavily forested hills, is a perfect example of this type of community.

Native Craft on the Ohio

Long before Europeans settled in the Ohio River valley, Native Americans made extensive use of the great river as a means of transportation. This was accomplished with the help of several kinds of watercraft, the most famous being the canoe. While many associate the canoe exclusively with the Native Americans, nearly all early explorers and settlers utilized this light and efficient craft to navigate the at-times treacherous Ohio.

Trees to Canoes

Though the design of the canoe differed from tribe to tribe all over North America, two distinct models were frequently used by the tribes along the Ohio River. The first was a type of heavy canoe made from a dugout tree trunk. Known as a pirogue in the south, the essential elements of its design were the same as that of its northern cousin. A large tree was selected, felled, and stripped of its bark. After trimming, the trunk was shaped and the hollowing process began. This was either accomplished with the ax, adze, and much labor, or by a specialized method of burning that weakened the internal structure of the log and made hollowing much easier. Though its construction was more primitive than other canoe types, the dugout was a strong vessel that could easily weather the numerous dangers of the river, including snags, rapids, and shallows.

The other common canoe type popular among Ohio River tribes was a lighter vessel constructed of large strips of bark, often birch, set around a thin inner wooden frame. This frame design proved to be an extremely practical way of keeping the weight down on the canoe, making it easy for a single person to carry. It also made the structure remarkably sturdy and balanced for its size, allowing the canoe to carry large loads even in shallow water. Though the dugout canoe was better able to withstand river hazards, the bark canoe’s light weight and increased maneuverability made it the preferred means of transportation for explorers, trappers, and settlers.

Canoes Were Practical to the Ohio

An advantage that canoes held over later craft was that with an experienced guide, often a Native American, canoes could run the Falls of the Ohio, as well as other famous problem spots with little difficulty. This was extremely important because larger vessels were often forced to tie up and wait for higher water in order to make the attempt. During the tension-filled days of the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and the ever-present troubles with native tribes, delays of this sort could prove disastrous to a remote settlement or beleaguered fort.

Despite the widespread appeal of the canoe to both Native Americans and Europeans, these early vessels were truly adequate only for short trips during periods of relatively calm water. This suited the native tribes, who used the vessels mainly for trips to their hunting grounds, for ferrying people and supplies across the river, and for journeying to councils or assembling for war. For centuries the inhabitants of the Ohio River valley had no need for more substantial transport and contented themselves with simple rafts and canoes. With the introduction of European settlers to the region, however, more substantial rivercraft were needed.

Pioneers Go West

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, many who sought to settle the west took ship, traveling from Pennsylvania, Virginia, Ohio, and Kentucky down the great river. Though settlers had been utilizing the Ohio for decades, the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and the 1804-1806 expedition of Lewis and Clark sparked a full-fledged migration westward. As settlers began to arrive from the east in large numbers, settlements sprung up all along the Ohio. While this lead to inevitable conflict with native tribes, it also presented the settlers with the problem of how to transport their families and belongings to their new homes. Overland travel was extremely slow and hazardous in this undeveloped country; therefore many settlers turned their eyes to the broad Ohio and the promise of speed and ease of travel that it offered.

As early as 1805 or 1806, adventurous pioneers, including some with their families, began settling on the location of present-day Madison.footnote 1 Some, more hardy or foolhardy than others, trudged dozens or even hundreds of miles along narrow paths carved through the forest by natives, but the vast majority chose to simply float down the Ohio. In canoes, flatboats, and keelboats, colonists ventured further and further west, eventually reaching the Mississippi River and its mouth at New Orleans, that great export center of the south. In this way, the Ohio River valley was permanently settled and before long its rich farmlands and thriving centers of industry proved to be a great asset to the young, struggling nation.

Early Madison Settlers

Among the early explorers and settlers of the site of present-day Madison was John Vawter, an enterprising man who would become Madison’s first justice of the peace as well as Jefferson County’s first sheriff. His father, Jesse Vawter, “with six or eight other Kentuckians from Franklin and Scott Counties, visited what was then called the New Purchase at a very early date [December, 1805]. A part journeyed by land and a part by water. The land party crossed the Ohio River at Port William [present-day Carrollton]; the others descended the Kentucky and Ohio Rivers in a pirogue to a point opposite Milton. The pirogue answered the double purpose of carrying forward the provisions of the company and enabling the men to pass from one bank to another, swimming their horses along the side.”

The elder Vawter’s experience was typical of most settlers of the day and as he returned home to Kentucky to prepare his family for the move, 24-year-old John decided to inspect the land for himself. Like his father, he traveled in a pirogue. “My second visit to Indiana was in May, 1806. I came in a pirogue and landed a little above the stone mill opposite Milton, visited the highlands east and west of Crooked Creek, continued at my father’s…to assist him in getting his corn planted, [and then] returned in the same craft with my mother and other relatives to Frankfort, Kentucky.”

Flatboats & Keelboats

Though the Native American canoe was convenient for early explorers and settlers, the craft’s size and carrying capacity made it unsuitable for the majority of pioneers who later ventured west.

The Journey West on the Ohio

Life in the crowded, dirty cities of the 19th century, as well as the allure of cheap land made available by a series of land grants and treaties with native tribes, lead many easterners to simply pack up their families and all their belongings and set off into the wild. Though they were a far cry from the solitary surveyor or trapper, confidently winding his way down the Ohio in a canoe packed with provisions, these waves of settlers nonetheless played an important role in populating the Ohio River Valley. Several such mass migrations in the late 18th and early 19th centuries meant that river travel quickly became one of the premier means of transporting a pioneer household to the frontier.footnote 1 To accommodate the heavier loads now carried by settlers, a series of much larger and stronger river vessels was needed.

The Use of Flatboats

The average colonist embarking on a journey down the Ohio had several types of rivercraft to choose from. The first, most basic, and most affordable of these new vessels was the boxy and awkward flatboat. It was so named because of its flat underside and shallow draft, which gave the hull the balance and strength to hold a large deck, but made the vessel difficult to steer. At anywhere from 8 to 20 feet wide and sometimes up to 100 feet long however, the flatboat was considerably larger than any previous riverboats.

The flatboat’s size made it a crucial component of Ohio River commerce from the 18th century onwards. Its large cargo capacity ensured that river trade from east to west boomed, but the vessels were primitive and suffered greatly from an inability to ascend the river against the current. This meant that trade between settlements on the Ohio River and the industrial bases further east or the export centers to the southwest could only proceed one way. Once a flatboat reached its destination, cargo would be offloaded and its fate was determined by the owner. Settlers often dismantled their flatboats, using the planks to build homes, while businessmen typically instructed their steersmen to salvage any intact boards to sell as scrap timber. The flatboat opened the eyes of many manufacturers and entrepreneurs to the lucrative opportunities offered by river transport, but the vessel’s design faults as well as its helplessness against the current of the Ohio made it less than ideal for the economic growth of a nation.

Use of Keelboats

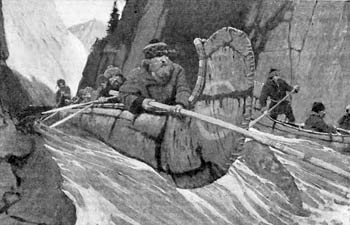

An improvement on the flatboat was the keelboat. Named for the keel, the longitudinal beam to which the “ribs” of the vessel were attached, the keelboat was a much stronger and more versatile vessel than the flatboat. This can be seen by the fact that a mainstay of the Lewis and Clark expedition was a 55 foot keelboat named “Discovery.” The great advantage of this type of boat over its predecessors was its ability to ascend the river against the current. To this end, the keelboat had a sleek hull and a pointed prow and was often equipped with a mast and sail to ease the ascent. If the wind was uncooperative, the ship’s crew, known as keelboatmen, took to the oars or more frequently to long poles. These they used to row or “pole” the boat up the river, while other crewmen helped to drag the boat forward by pulling on overhanging tree limbs. If such backbreaking work still failed to propel the vessel upstream, a party of men would be forced to land on the riverbank, secure a rope to the keelboat, and tow the craft by hand. Despite the arduous nature of their return journeys, the keelboat was a more advanced and less expendable vessel than the flatboat. Its design often sported a covered superstructure or even cabins for the passengers and crew. This at least made the long, slow voyage back up the Mississippi or Ohio a little more comfortable.

Conclusion

The end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th witnessed not only the rise and the zenith of flatboats and keelboats on the Ohio, but also their decline. While these vessels delivered their cargo and plied the treacherous waters of the great river, the device that would replace both and come to dominate the great rivers of America was born: the steamboat.