Prior to the establishment of railroads in the Ohio River Valley, the explosively expanding trade in produce and manufactured goods with the Eastern and Southern parts of the country made mass river transport a necessity. To speed the process of moving goods and people along the great waterway, several engineers and inventors developed early versions of the steamboat. These devices drastically reduced transit time and increased carrying capacity, ensuring higher profits and in turn a solid foundation for the American economy.

Steamboat Development

As far back as the first century, ancient inventors were experimenting with the power of steam. An Alexandrian Greek may have even fashioned a simple spinning toy, powered by a cauldron of heated water, and unknowingly unlocked the secrets of steam power. Although the ancients did not realize the amazing possibilities offered by their amusing inventions, the field of steam power would eventually become the catalyst that drove the development of much of the modern world. For the most part this was done through transportation, which boasts far more ancient roots.

Mankind has turned to the sea for trade and travel for thousands of years, but by the 4th century, boatwrights in Europe were seriously engaged in developing a more efficient means of propulsion for their vessels. Side and center paddlewheels were long-thought to be the future of ship impulsion, but despite the best efforts of Roman engineers to design an ox-driven craft or Leonardo da Vinci’s hand-cranked conception, a constant and even force was necessary to successfully drive such a vessel. Modern attempts in both Europe and later in America began in earnest in the 16th century, but as before, paddlewheelers proved impractical without a consistent and reliable source of power.

Steam Engine Development

By 1769, James Watt had provided inventors with just such a power source when he patented an improved version of the steam engine. By 1782 he moved beyond simply improving older models when he invented the double-acting steam engine, effectively doubling the machine’s power output. In an age before high-pressure steam, Watt’s invention was a quantum leap forward in engine design. His innovation was rapidly adopted by the numerous different hands at work on the initial steamboat models. Unfortunately for the modern historian, several men were simultaneously at work on designs for a steam-driven paddlewheeler. By the 1770’s and 1780’s, numerous experiments had been carried out in Europe to prove the viability of steam as a power source, but despite these successes, early attempts at steam-powered rivercraft were met with incredulity and viewed as mere curiosities. It was entirely due to the exertions of inventors and promoters like John Fitch, Robert Fulton and others that the steamboat eventually asserted itself as the premier means of conveying passengers and cargo both down and up America’s mighty inland waterways.

The Economic and Industrial Impact of the Steamer

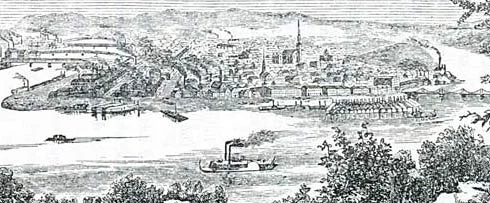

In the early years of the 19th century, America was still recovering from the ravages of war with Britain and, though nominally at peace, international tensions kept the young economy weak. As it struggled to stand under its own power, the country’s fragile finances were given a much-needed boost by the slowly-realized applications and capabilities of the steamboat. Not only could surplus crops be quickly and easily shipped off to market, markets much further away than before, but a whole new industry, centered around the steamboat itself, promptly grew up. With their large hulls, complex machinery, and ravenous fuel consumption, these lumbering machines required many new services and facilities in order to stay afloat. While existing industrial centers vastly expanded and altered their works, machine shops and engineering schools began popping up in many large river cities. In a short time, shipyards and steamboat services became one of the quickest ways to ensure a town’s commercial success and economic growth. Madison joined this bandwagon around 1835 with a small shipyard in the eastern suburb of Fulton,footnote 1and by the 1850’s and 1860’s had developed a thriving shipbuilding industry with the completion of a newer yard and drydock at the other end of town.

Once the steamboat had firmly established itself on the Ohio River, industrial ports like Madison boomed. From the 1820’s on, wool, cotton, flour, and sawmills made the city an important center of trade, while breweries, foundries, starch factories, and many other businesses grew off the success of the thriving town. Crops and goods flowed into Madison from the state’s interior to be shipped to bigger markets in Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Louisville, New Orleans, and other towns all along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. In the words of one locally-compiled history, “It is almost impossible to overestimate the benefit the shipyard has been to Madison.”

America Embraces the Steamer

With the steamboat, the founders of America finally had the means of uniting the fledgling nation. Once the innovation had proven itself reliable, packet service was established, whereby individual boats known as “packets” ran on scheduled timetables. This allowed the public to take advantage of a boat’s shipping course to move around the country. With easy trips between ports a reality, the great age of American travel was born.

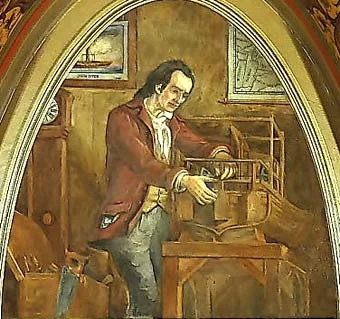

John Fitch

The confusion and disagreements of the early days of steamboat experimentation are nowhere more clearly seen than in the unfortunate life of John Fitch.

Working feverishly in his Philadelphia workshop from the mid 1780’s to the early 1790’s, Fitch developed the first practical American steamer just before his rival, James Rumsey. This lead to a court battle for the patent rights from which Fitch eventually emerged victorious in 1791. Despite this success, and his accomplishment in establishing the first regular packet steamer in the United States in 1790, Fitch never truly succeeded in the steamboat business. Few people recognized the value of his passenger steamer, despite its successful packet career, which ultimately covered thousands of miles in short, timely, and comfortable trips. Though he went on to develop several different kinds of steam-powered vessels, experimenting with various styles of drive mechanisms, Fitch was weakly funded and in the end he was unable to convince either the public or the industrial business community to regard his invention as anything other than a curiosity.

In 1798, just seven years after he had patented America’s first steamboat and unknowingly launched a revolution in transportation and commerce that was to radically shape the course of American history, John Fitch, despairing at a life full of failure and sorrow, committed suicide. In the years to come, Fitch’s innovations inspired other engineers to modify and perfect the design of the steamboat, and sadly, the success of these models helped to eventually eclipse the memory of his achievements altogether.

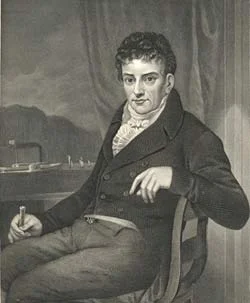

Robert Fulton

While John Fitch proved that a working model of the steamboat could be built and used on America’s rivers, more than anyone else of his era, Robert Fulton deserves credit for changing the image of the steamboat from that of a frivolous novelty to a commercially lucrative and socially desirable means of transportation.

Fulton’s background as a self-made engineer, his work on Britain’s canal system, and his experimentation in the cutting-edge field of submarine warfare sparked a deep interest within him in the possible construction of a steam-powered rivercraft. In 1802 Fulton, fascinated and enticed by the possibilities of an emergent America united by this new and exciting technology, partnered with the American minister to France, Robert Livingston, to secure the exclusive rights to operate a steamboat in New York waters. Modern historians delight in reminding many who would now idolize Fulton that during his lifetime he was anything but idolized, most especially by the common riverman. Fulton’s monopoly of steam-power in the northeast and his attempts to gain similar control of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers led to outrage among bargemen and boat-hands of all types of vessels whose livelihoods were threatened by this new contraption and its ravenous owner.

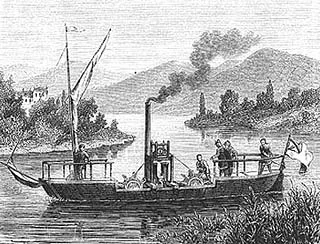

Despite the outcry from river communities, it seemed that everyone not directly affected by the monopolies were delighted and captivated by Fulton’s energetic experimentations. By 1807, Fulton and Livingston had triumphed with the construction and test run of a steamboat on the Hudson River. Commonly called theClermont, this vessel was not named such by Fulton, who called the vessel theNorth River Steamboat and later the North River Steamboat of Clermont. Regardless of its name, Fulton’s first steamboat was quickly established as a packet steamer and proved to be a great success. With this experience firmly tucked under his belt, Fulton set his sights on a much more lucrative area, the Ohio-Mississippi River trade with New Orleans.

The Voyage of 1811

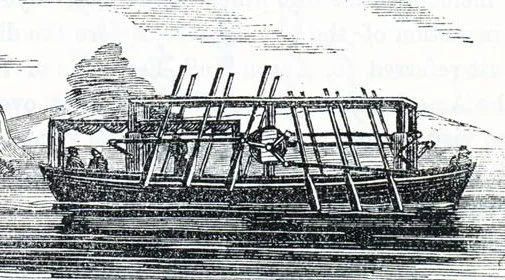

Fulton and Livingston realized that while their work on the Hudson was a breakthrough, introducing their controversial machines on the Ohio and Mississippi was a whole different ball game. Not only were these rivers much larger and more dangerous to navigate than the Hudson, but there was also a significantly higher number of river communities to persuade of the steamboat’s merits. Livingston and Fulton planned to meet these challenges by constructing a steamboat in Pittsburgh that would then steam down the Ohio into the Mississippi, demonstrating its revolutionary workings and uses along the way. The steamer would then take up its assigned task, ferrying goods between the cities of New Orleans and Natchez. In 1809, Nicholas Roosevelt, a boat-builder and early American proponent of the steam engine, was charged with scouting the currents and perils of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers prior to any serious investments by Livingston and Fulton. Roosevelt and his pregnant wife Lydia made the treacherous voyage on a flatboat over the course of six months whereupon they reported back that the rivers, though hazardous, were indeed suitable for steam navigation.

Early during the momentous year of 1811, a year in which the Napoleonic wars still raged across Europe and many South American countries declared their independence from Spain, work began in Pittsburgh on the first steamboat ever to ply America’s rivers west of the Alleghenies. In March, just as the Great Comet of that year was detected in France, the hull of Fulton’s vessel was launched. (footnote 1). It remained only to construct the boat’s superstructure, retrofit the hull with its side-wheel paddles, and install the complex engine machinery. While this work progressed during the spring, summer, and early fall, the comet drew near and record flooding and epidemic outbreaks along the Mississippi caused great panic among the inhabitants. By Sunday, October 20 the comet had achieved it maximum brightness in the night sky and the steamboat, newly dubbed the New Orleans for the boat’s ultimate destination, steamed out of Pittsburgh into the Monongahela heading for the Ohio. (footnote 2)

Reactions to the New Orleans

As the New Orleans descended the river, traveling beyond the area where its construction was widely known, curious crowds lined the banks, eager to catch a glimpse of this strange new device. Even in the more technologically advanced eastern states there could have been relatively few Americans who had ever seen anything like it. With its paddle-wheels thrashing the water and engines loudly grinding, several frightened onlookers, familiar with the steam engine only from the local lumber mill, reported that a “sawmill” was traveling down the middle of the river. As the New Orleans wound its way downstream at the frightening speed of from eight to twelve miles an hour, horseback couriers dispatched to spread the news to downriver communities were often beaten to their destination by the vessel. One can only imagine the wonder and fear that such a craft would produce among the simple farmers of the Ohio valley.

As the New Orleans neared Cincinnati on October 27, a frantic horseback messenger managed to reach the city and warn the citizenry that “a boat driven by elastic vapor was approaching from up river and all who could ought to go down to the river bank and see it.” With this prompting the city of Cincinnati essentially ground to a halt. “Down to the river bank they poured. They closed their stores and shops and let business go hang.” In a very short time the shore was swarming with massive crowds. “In a little while the boat was at the landing, but staying off shore at Capt. Roosevelt’s command, for he feared if a crowd came aboard, his craft, which was none too certain on its bottom, might capsize, and he refused to let anybody come aboard, although scores put off in any kind of boat available to look this strange vessel over.” Unlike the residents of Cincinnati, the people of Madison had no warning that a steamboat had even been built, let alone that one would be passing their quiet little settlement on its way downstream to Louisville.

The New Orleans’ trip past Madison was heralded with “a noise like the firing of a gun.” Several men, who were fishing along the river’s edge at the time, heard the blast and looked in “the direction of the Kentucky shore. At the same time a strange looking craft rounded the point.” With the extraordinary happenings of that year still foremost in their minds and more recent news of intensifying native attacks (footnote 3) the men did what anyone would do if confronted by such a strange vision. “They immediately dropped everything they had with them and made haste for town. They ran until out of breath and then hid under some logs for a time. But finally, becoming more alarmed, they broke from cover and ran through the woods, entering the town streets in wild excitement, crying that the Indians were coming up the river.”

Further downstream near Louisville, news of the increasing tensions with Great Britain led residents to leap to a different conclusion about the threatening contraption coming down the river. “The family was one day much surprised at seeing the young Mr. Weldons running down the river much alarmed, and shouting, ‘The British are coming down the river!’ There had of course been a current rumor of war with that power. All the family immediately ran to the bank. We saw something, I knew not what, but supposed it was a saw mill from the working of the lever beam, making its slow but solemn progress with the current. We were shortly afterwards informed that it was a steamboat.” Arriving at Louisville around midnight on October 29th, the steamboat woke the citizens and drew a large crowd with a sharp blast from its relief valve. The sound was so loud and unnerving that some residents “insisted that the comet of 1811 had fallen into the Ohio and had produced the hubbub!”

Success and Disaster

Upon reaching Louisville, the captain and crew realized that with the deep draft of the hull, they would have to wait for the river to rise in order to pass the treacherous Falls of the Ohio. This free time allowed the New Orleans to demonstrate its revolutionary workings by steaming back upriver to Cincinnati, confounding many in that city who had declared that they would never see the steamer again. By December 8, the water level of the Ohio had risen sufficiently to allow the New Orleans to pass with a mere 5 inches of water between its hull and the jagged rocky bottom. The crew and captain were delighted to again be under way, but their happiness was almost immediately marred by a natural disaster of epic proportions. In the early morning hours of December 16, the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys were rocked by the first of a series of three earthquakes that are estimated to be the strongest ever recorded in the continental United States in historical times.

“The first shock that was observed was felt on board the New Orleans while she lay at anchor after passing the Falls. The effect was as though the vessel had been in motion and had suddenly grounded. The cable shook and trembled, and many on board experienced for the moment a nausea resembling sea sickness. It was a little while before they could realize the presence of the dread visitor. It was wholly unexpected. The shocks succeeded each other during the night.” Despite this harrowing account, the steamboat and its passengers fared far better than the people on shore. Geologists today conclude that the New Madrid earthquakes of 1811 and 1812 registered at least an 8 on the Richter scale and were strongly felt over an area of 50,000 square miles. This is substantiated by reports that the shocks caused church bells to ring as far away as Boston, Massachusetts.

In the immediate vicinity of the epicenter, the ground rolled like ocean waves, splitting into chasms, submerging into lakes (such as Reelfoot Lake in Tennessee, pictured) or heaving up in some places as high as fifteen to twenty feet. The earthquake proved even more devastating along the course of the Mississippi River, the current of which was seen to reverse itself for some time. The river the New Orleans steamed down after the earthquake was one substantially changed from that of only a few days before. Along much of the river, banks had collapsed, islands sank or were formed, and hundreds of tree trunks lying on the river bed for years were shaken into an upright position, presenting an extremely hazardous challenge to the pilot and captain of the New Orleans to navigate.

The scale of the earthquake’s impact on the region can be judged by the fact that the steamboat’s pilot, Andrew Jack, an experienced navigator, was often confused by a lack of any visual aides that he recognized. “One of the most uncomfortable incidents of the voyage was the confusion of the pilot, who became alarmed, and declared that he was lost; so great had been the changes in the channel caused by the earthquake. Where he had expected to find deep water, roots and stumps projected above the surface. Tall trees that had been guides had disappeared. Islands had changed their shapes. Cut-offs had been made through what was forest land when he saw it last.” Despite the extreme danger this posed to the craft and crew, the delay at the Falls of the Ohio left no room for further holdups. Through dangerous new channels the New Orleans steamed down the Mississippi, amid the chaos of devastated towns and desolate farmland. The pandemonium seems also to have spread to the naturally warlike Chickasaw, who, fearing the steamboat as a manifestation of the great comet (footnote 4) and believing it to be the cause of the earthquake, attacked the New Orleans in a war canoe. The captain ordered full steam and the vessel eventually outran the natives, who “with wild shouts…gave up the pursuit, and turned into the forest from whence they emerged.”

After this adventure the crew was immediately greeted with another near-calamity. During the night a careless servant left some wood too near the stove in the forward cabin. This caught fire and it was only through the frantic efforts of the captain and crew that the boat was not burned to the waterline. Happily, the fire did not cause irreparable damage to the vessel, and apart from some still-treacherous stretches of the Mississippi, the New Orleans faced no more serious dangers.

Arrival at New Orleans

The New Orleans arrived at New Orleans on January 10th, 1812 to a warm welcome. Upon reaching its namesake city, the boat began a successful career as a packet steamer and shipping vessel, running from New Orleans to Natchez and back for over two years.

In the space of only a few short months, the New Orleans ensured that river life in America would be changed forever. Even with the considerable delay at the Falls of the Ohio, the journey of the Midwest’s first steamboat was much shorter than that of most river vessels of the time. Up and down the great rivers, theNew Orleans terrified and delighted the crowds that lined the banks to catch sight of it. What those spectators witnessed was not just the first steamboat on western waters, but the economic birth of America. Until the advent of the railroads in the late 1830’s, steamboat shipping proved to be the fastest and cheapest way to move goods and passengers around the country. With this system of transport in place, America was able to rapidly industrialize, by the time steam transport began to fade in the 1860’s, the country was firmly set on a course for economic prosperity.

In opening America’s waterways to trade, transport, and travel, the New Orleans blazed a path down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers for countless other steamers to follow, but sadly, the brave little vessel did not survive to see the heyday of its descendants. On July 14, 1814, the New Orleans was caught on a snag in mid-channel and foundered. Her captain, crew, and passengers escaped unharmed but the ship that had faced so much criticism and overcome so many obstacles on her great voyage was lost. (footnote 5)