Home > River to Rail > Rail Stories

River To Rail: Rail Stories

Tales From Madison's Rails

There are a multitude of stories related to Madison's railroads. Let's start at the beginning of the 19th century when life in Ireland was harsh and cruel. With nothing in store but starvation and persecution the Irish began to immigrate to America... and work on the Madison & Indianapolis Railroad.

These are just a few of the stories...

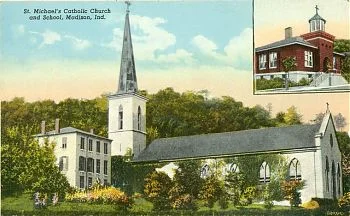

Irish Hollow & St. Michael's Church

At the beginning of the 19th century life in Ireland was harsh and cruel, due mainly to the English yoke pressed to the Irish neck. With nothing in store but starvation and persecution, the Irish began to immigrate to America.

The first trickle of Irish was assimilated into the American culture but when the trickle became a flood, the Irish were met with suspicion and hostility. “No Irish Need Apply” was posted with each job opening advertised. The Irish found themselves being exploited by the unscrupulous and shut out by the bigoted. They were relegated to the most demeaning and menial jobs at the lowest pay.

When work was offered in the coal mines and on the canals and railroads in the east and the midwest, the Irish readily accepted. It was said that an Irishman was buried under every tie. Under these circumstances and in this atmosphere, the Irish began to congregate together, building shantytowns along the railways. In Madison their gathering place was evidently “Irish Hollow.” The name is all that remains of the place. It was located on the flat area running to the edge of Crooked Creek and just east of what is now State Road 7, or Hanging Rock Hill. The railroad cut would have passed just to the west of the hollow.

We have little information about the hollow during the building of the railroad but it was probably built of unsubstantial and temporary dwellings for most of the workers would move on with the railroad when the work “played out”. There may have been a store for “staples” and pipe tobacco and such and there would have been a few saloons, or, as the Irish called them, pubs. It’s likely conditions would have been poor and that pestilence and fever carried off as many souls as did the railroad.

They would have felt the lack of a church deeply and being a determined and resourceful lot, they began to store the stone torn and blasted from the railroad cuts. It was hauled to the end of Third Street where it was piled and dressed and there the Irish began to build their church, St. Michaels. The Catholic priests in the parish probably prevailed upon the famous architect, Frances Costigan, a member of the congregation, to design the church. Since little money was available for other materials needed, the good Irish women raised money by tending feeder pigs to sell. They gathered the swill from the starch factory and hauled it in wooden tanks on ox carts to fatten the hogs. The hogs were sold at local markets and the money was donated to the church. In 1837, their efforts resulted in the beautiful Gothic style church that still stands today as a tribute to those early Irish immigrants.

Indiana Railroads

With the 1836 Interior Improvement Act, railroads were slated to criss-cross the state. “Read more” for the list of early Indiana railroads.

Bellefontaine & Indianapolis: Begun in 1848, by 1852 it connected Indianapolis to the east and northeast.

Indiana Central: Begun in 1851 and completed in 1853. It ran from Indianapolis to Richmond and made the run from Terre Haute to Richmond possible.

Indianapolis & Lafayette: The 1836 internal improvements acts included Lafayette on the Madison & Indianapolis line. Completed in 1852 it helped connect the Ohio River to Chicago.

Jeffersonville Railroad: Chartered in 1832 but due to financial difficulties it was re-chartered and because of delays not completed until 1852. It was in direct competition with the Madison & Indianapolis and the two lines merged in 1866.

Lawrenceburg & Indianapolis: Chartered in 1832 but not completed until 1853. Made connection between central Indiana, Cincinnati and points east.

Madison, Indianapolis & Lafayette: Chartered in 1832, begun in 1836 and finished to Indianapolis in 1847.

New Albany & Salem: Later called the Monon, this line was the longest in the state prior to the Civil War. It eventually connected the Ohio River to Lake Michigan and Chicago.

Ohio & Mississippi Railroad: Spanned the southern part of Indiana from Cincinnati to Vincennes and made possible connections from Baltimore to St. Louis. It was completed in 1857.

Peru & Indianapolis: The function of this line was to connect Indianapolis with the Wabash & Erie Canal. It was completed in 1854.

Station Bell

The bell was cast at the Gerret Foundry in Cincinnati in 1849 and was installed in the cupola of the newly constructed passenger depot that same year. The upper part of the bell is decorated with an ornate frieze of allegorical figures representing the progress of the world in art, letter and transportation. The bell was rung half an hour and again five minutes before the departure of passenger trains from Madison to warn travelers to make their way to the station.

At some point in the 1880’s the bell was diverted to Richmond, Indiana by John F. Miller, a PCC & ST. L Railroad official. For many years it languished in an obscure spot at the old train station there. The town benefactress, Drusilla Cravens, granddaughter of one of the original signers of the 1832 charter, obtained the bell and restored it to the town. Arriving here in time for the Indiana Centennial, the bell was placed on display next to the railroad station and in 1935 it was moved to City Hall where it resided until 1944. It was then placed in storage at Clifty Falls State Park but in 1953 it was located on the lawn of the Lanier Home atop a stone burr from Clifty Falls Mill. In 1991 the bell was given by the State of Indiana to the Jefferson County Historical Society and it now resides in the restored railroad depot.

Cooking Stoves & Uniforms

One reason the rank and file got up in arms…

In 1882 at least two notable innovations took place on the J. M. & I. Railroad, the first being the installation of a cooking stove in the caboose of each train and the second being that its conductors, baggagemen and brakemen should be clad in “new” and appropriate uniforms. The obvious reason for cooking stoves in the caboose was so that workers could fix their meals cheaply and avoid the cost of a hotel room at the end of the line. The cynical, however, might be of the opinion that having cook stoves on the trains meant there would be no reason for workers to be tempted to lift a few beers or get into mischief while off the job. It didn’t hurt either, that the new innovation guaranteed employees to be close at hand and ready to work at a moment’s notice. It was the equivalent of having a live in maid on call at all times. The addition of consistent and more conspicuous uniforms, one would surmise, made it easier to identify railroad employees and give the public a feeling of assurance and convenience of identification. Each position of employment would enjoy its own but distinctively homogeneous attire. No more would the road allow the various assortments of overhauls and patched pants, or the flannel shirt with elbows protruding. This was, after all, the Victorian era, with refinement and sophistication being the order of the day. The idea had come of age on other railroads and could the J. M. & I. do less than doggedly follow suit?

The uniform consisted of pants, vest, coat and cap, all of an appropriate dark color (no doubt a good choice to conceal the accumulation of soot) with the appropriate insignia for each classification. On the lapels of the baggage master was a shield, inside of which the monogram “B. H.” was neatly embroidered. The coats of the conductors were more elaborate and “fearfully got up” and could be mistaken in any crowd for the uniform of a rear admiral or major general. The uniforms were, however, evidently a source of pride to the new owners, for the Columbus Herald related, “when Scott Thomas got here this morning from Madison with his fine uniform, he jumped off his baggage car and ordered the boys around at a lively rate. “Major General” Elliott (Calvin) felt so big that he inquired what little one-horse village this was that a train commanded by such a good looking crew should be bored with stopping at. He failed to recognize any of his old acquaintances until he was formally introduced”.

This tongue in cheek taunt was all well and good but the railroad was dead serious as to the proper presentation of its new standards. Clean, pressed and well-turned-out, that was the order of the day. Woe be to any who did not conform, even for a moment. One unlucky employee was laid off for thirty days for doing switch work on the main line with his coat unbuttoned. This high-handed attitude, however, backfired when the local paper issued this comment, “If for this trivial offense, a man is laid off thirty days, there must be a sliding scale of punishment for non-observance of the rules and regulations for wearing these railroad liveries. For instance, to appear with the top button out of place, two days would be about the proper caper; the second, six days; the third, fifteen days and the fourth, thirty days. One breeches leg rolled up, four months, and to appear before the big bugs without a coat, instant death! Such aping of royalty in free America is simply disgusting, and is opening the eyes of the rank and file in this country.”

This was a telling and prophetic statement. In the coming years the railroads would lose their iron grip on the workers, but in 1882 the careless unbuttoning of a jacket meant the loss of a month’s pay. The rank and file would have to bide its time until the organization of a powerful union would protect the railroad worker.

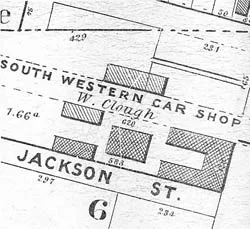

Southwestern Car Shop

Early in June of 1851, William Vincent Clough and Joseph Farnsworth obtained a “suitable” lot in the west end of Madison near the riverfront where they could erect a large building for the manufacture of railroad cars “of every description”. On June 26th the construction of the building began. The original building constructed was two hundred feet by sixty feet and was calculated to employ forty to fifty workers. The new enterprise was christened The Southwestern Car Shop. Late that year the first cars were produced.

Farnsworth, who was also associated with the Madison Foundry, was already making railroad car wheels for railroads in Ohio and the interior of Indiana. It seemed only proper that the building of an entire railroad car would be advantageous and profitable, especially since the shops of the Madison road had been frequently put under requisition to furnish cars for the roads connected with it.

Indeed, the business seems to have been an early success. The location, being near the terminus of the Madison & Indianapolis Railroad and on the Ohio River, proved to be an advantage and orders must have been all the two men had hoped for because the original building quickly expanded into a “complex” of buildings by 1853. In 1853 and 1854 the company advertised in the American Railways Times, “Passenger Cars, House Cars, Cattle and Hog Cars, Gravel Cars, etc.” for sale. Sometime before 1857, for unknown reasons, Farnsworth must have sold his portion of the business to William Clough because from that point on there is no reference to him as co-owner. William Clough, still a young man in his twenties seems to have been a good business manager, however, because on June 1, 1857 the Madison Courier noted that, “Clough is sending, in flatboats, another lot of railroad cars for the New Orleans, Jackson & Great Northern Road, making an aggregate of seventy-five cars sent to this road from his establishment since 1st March. There are four superb passenger cars nearly completed for the same road; and in process of construction, passenger cars for the New Orleans and Opelousa and Great Western Road, for the Vicksburg and Texas, and for the Southern Pacific Roads. There is no establishment in the state in a more flourishing condition than the Southwestern Railroad Car Factory”. The car shop was, no doubt, still riding the “bubble” of prosperity with which Madison had been so blessed. But as the bubble began to deflate, it would seem orders and subsequent profits began to dwindle, also. In the panic of 1857 many of the southern roads the car shop was dealing with went into bankruptcy, dealing the shop a blow from which, it would seem, it never recovered. The shop closed its doors somewhere around 1860 and on August 21, 1863, the newspaper announced, “Mr. Vawter, the purchaser of the Southwestern Car Shop, has been for about a week past engaged in refitting the establishment. The Shop, which is quite extensive, was formerly, as most readers are aware, owned by Mr. Wm. Clough, who did a large business in the way of car building, etc. Adverse times setting in, the proprietor was obliged to suspend operations, and for years the establishment has been closed. The property at recent public sale passed into the hands of Mr. Vawter, who is repairing and fitting it up, intending to convert it into a mammoth Planing Mill.”

In April of 1867 the old car factory, or at least a good portion of it, fell down from the immense weight of starch placed in the second floor by one of the local starch factories. It was propped up for use as a warehouse for a time but the constant flooding of the Ohio River and prolonged neglect that the buildings sustained soon took their toll. The building, or buildings, fell into ruin and, as with many of the structures along the riverfront, without any fanfare, faded into oblivion.

William Hoyt: A Day Late & a Dollar Short

There was, at one time, a great controversy pertaining to the invention of an improvement to the cog rail system used on the Madison incline. It seems Andrew Cathcart, master mechanic for the M & I, and William Hoyt both claimed the invention. The railroad evidently paid both men for the rights to the mechanism; Cathcart receiving $6,000 and Hoyt a mere $1,000. This seems to have “stung” Mr. Hoyt as he offered this article in the Madison Daily Banner: “ TO THE PUBLIC – I noted a communication in your paper of the 5th of July concerning this new and useful invention for ascending incline planes on railroads, in which the writer refers me to what Columbus said, viz: It is a very easy thing to make an egg stand on end when we have once been shown how. My reply to this is that I, William Hoyt, of Dupont, Jefferson County, Ia, laid a noble egg, Columbus like, on its end, on the Madison inclined plane in 1839, and have sat on it until 1848, and the egg was about to hatch when one Andrew Cathcart, a Scotchman, slipped on my nest, and, by the assistance of our worthy directors, has hatched out the chicken and is now living sumptuously on the fowl, while I have not as yet had a chance to suck the tip of the wing.”

George S. Cottman looked into the controversy by inspecting the patents each man applied for and in an article for the “News” dated April 15, 1922, he reported: Patent #6321, dated April 17, 1849 contained specifications of a “cog gearing of locomotives for ascending inclined planes” claimed as the invention of William Hoyt of Dupont, Indiana. He continues: Patent #6818 dated October 23, 1849, contains specifications of an “improvement in locomotives for ascending inclined planes.”

Hoyt’s patent was of the earliest date but Cathcart contended his invention was slightly different than Hoyts’ and Hoyt maintained Cathcart had modified his, Hoyt’s, invention. The dilemma was never satisfactorily resolved. The railroad, however, continued to use the mechanism, staying above the fray.